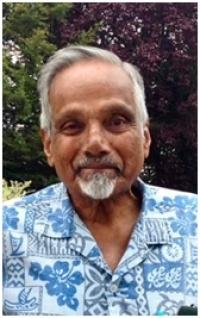

VOZKEN ADRIAN PARSEGIAN of AMHERST, MA, May 28, 1928 – July 5, 2023

VOZKEN ADRIAN PARSEGIAN of AMHERST, MA, May 28, 1928 – July 5, 2023

Adrian Parsegian

May 28, 1939-July 5, 2023

AMHERST, MA. Vozken Adrian Parsegian was born in Boston. His mother, an Armenian immigrant, traveled all the way from Brooklyn so that her son could have “Boston” on his birth certificate. Adrian grew up in Brooklyn, attended Stuyvesant high school, then graduated magna cum laude in physics from Dartmouth College. He earned his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1965 after doing his thesis research at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel under Aharon Khatchalsky Katzir. There’s a famous story that when Adrian arrived, he was told that Aharon was lecturing. “I will just go listen to his lecture,” said Adrian. “But it’s in Hebrew!” replied the secretary of the Polymer Department. “That doesn’t matter,” said Adrian, who knew as yet not a word of Hebrew. (He did speak Armenian and eventually was even able to lecture in Hebrew.) He returned to the secretary, who asked, “well, did you understand anything”? “Oh yes,” said Adrian. “There were only three words I did not understand.” He produced a napkin with three words written: KEN, LO, OO-LIE (yes, no, maybe). All the other words, like “entropia” or “polymerim,” were comprehensible to a physicist.

Later, another anecdote started to make the rounds. When Adrian began his novel explanations of x-ray diffraction (the physics of forces,) he presented his findings at a seminar. “You can’t do that,” growled an eminent physicist. “But I just did!”

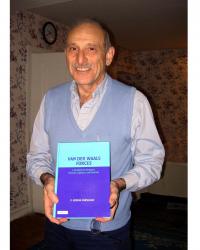

Adrian did his post doc with Irwin Oppenheim of MIT, mostly at the University of Amsterdam. Then he went to work at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, where he eventually became head of the Laboratory of Structural Biology. It was an intense, dedicated group of scientists from around the world, working together during those happy days. Adrian also wrote a successful book on van der Waals Forces (Cambridge University Press), typically titled “A Handbook for Biologists, Chemists, Engineers, and Physicists,” designed for use at three levels of expertise, all cross referenced. It was a publishing success, not least because Adrian insisted that the paperback edition (for students) be sold for $40. He would forgo his royalties to keep the book available to those who could use it. Those who remember how wildly expensive textbooks were (and are) will appreciate the “yes, I can” quality of Adrian’s publishing experience. Later on, teaching an advanced physics course at the University of Massachusetts, he gave copies of his book to his students.

Adrian was founding editor of the Biophysical Discussions. That was actually a successful experiment enforcing interdisciplinary exchanges, modeled on the Faraday Society meetings (no talks, only discussion of submitted papers, with the edited questions and answers published with the research papers in the Biophysical Journal). Here, too, Adrian ran into “you can’t do that,” and prevailed. As editor of the Biophysical Journal, he wanted to see how the actual product was published (by the Rockefeller University Press), and journeyed to Philadelphia to watch the presses running. (This was in 1978). He saw the final text being put into a computer for typesetting, and observed, “but those papers were already generated on computers. Why are they being retyped? Can’t we just use the digital material already typed in by the scientists? That meant collecting everyone’s floppy discs (then) and then figuring out how to utilize the various sources – KayPro, IBM, even Osbornes, UNIX, CPM, and DOS, and a little square device called a Macintosh. But Adrian worked in the Computer Division at the NIH and with their expert help he figured out how to make direct use of the already-created document files. Figures and photos still had to be done the old-fashioned way, by plates, but the main texts no longer needed to be painstakingly retyped, and copyeditors no longer had to spot a host of new errors introduced by the retyping. “You can’t do that” became “wow, you saved us a ton of money and time.” The Biophysical Discussions came out as a journal issue only a few months after the meeting itself. Adrian was elected President of the Biophysical Association.

The University of Massachusetts at Amherst had been wooing Adrian for some time, offering the position of a new Gluckstern Professor of Physics. Adrian had enjoyed his year of teaching physics at Princeton, and thought he might like to try his hand at teaching again. As he said when he came to UMass, “the work at his NIH lab measuring forces between and within large molecules can also be expanded into many student projects.” When he received an honorary doctorate in Spain (2008), in his acceptance speech he observed that he always got his best scientific ideas hiking with friends and colleagues. Mostly, he was to be seen pedaling along on his non-fancy bicycle. He celebrated his Dartmouth 50th reunion by biking with three classmates all the way from Amherst to Hanover.

Adrian and Val celebrated their 60th anniversary in March of this year. They have three sons, Andrew, Homer, and Aram, and three grandchildren, Seth, Benjamin, and Lauren. In later years Adrian developed non-Alzheimer’s dementia and slowly declined, ending eventually in the care of the Fisher Home (Hospice) in Amherst, where he passed away on July 5, 2023. He donated his brain to the Massachusetts General Dementia unit.

Hiking will be his last adventure. He showed his sons exactly where, on Mount Washington, he wants his ashes to continue their journey.

MEMORIAL GUESTBOOK AT: http://www.douglass funeral.com